Origins of a Catalan Technical Museum

Barcelona has been recognized as one of the most important industrial sites in Spain, yet this history has long remained under-represented museologically in the city. The first plans for a national technological museum, the “technotheque” arose in the 1930’s, championed by the Association of Industrial Engineers of Catalunya, who sought to legitimize their discipline and contribute to the shaping of the emerging national identity of the Catalan state: “making technology Catalan, and at the same time making Catalonia a technological nation” (Sastre and Valentinez). This project, intended for the slopes of Montjuic after the 1929 International Exposition urbanization, fell by the wayside after the Civil War.

Beginning of the Industrial Heritage Movement in Spain

Franco’s death and the transition to democracy marked the rebirth of these plans. In 1982, the Department of Culture of the Generalitat of Catalunya assumed the project and, in 1983, purchased the modernist-style Aymerich factory in Terrassa to be its home. The year 1982 also marked the convocation of the first “Jornadas sobre la Proteccion y Revalorizacion del Patrimonio Industrial” which were held in Pais Vasco and, three years later, in Catalunya.

Problems with Industrial Heritage

The expansion of traditional heritage categories (art, religious, architectural) to include industrial artifacts posed new problems: factory stuff was too vague of a category, too modern, not special or pretty enough, and lacked recognized experts to validate and interpret it. Furthermore, at this time, doubts existed as to the relative success, or even existence, of the industrial revolution in Spain. These conferences provided a platform for debating these issues and for promoting a new class of experts with the founding of the discipline of Industrial Archeology in Spain.

Industrial Heritage: a banner for Catalan Nationalism

In 1985, the exposition “Catalunya, la Fabrica de Espanya”, curated by the chair of Economic History at the University of Barcelona, Jordi Nadal, made a case for Catalan industrial pride by numerically comparing Catalunya with Northern European countries in terms of industrial potency during the 19th and 20th Centuries. The use of data, maps, graphs, and charts which demonstrated the competitiveness, and in some cases even superiority, of Catalan industry became a foundational work, setting the tone for later discourse regarding the national value of industrial heritage.

Another step was taken with the publication in 1984 of “Arquitectura Industrial a Catalunya”, a photographic study of factories built in the distinctly Catalan modernist style. The 1990 exposition “Modernisme Industrial”, created for the 1st Jornades de Arqueologia Industrial a Catalunya, echoed this architectonic focus. Together, these efforts represent an early trend in the industrial heritage movement of weighting value towards visual elements and favoring the exceptional over the typical.

Factory Re-use

During the transition in the 1970’s, citizen interest in Barcelona’s industrial sites arose in response to the need for new democratic facilities such as social centers, ateneos, libraries, and schools. The neighborhood associations of Sants, for example, succeeded in saving the factory “El Vapor Vell de Sants” by having it listed as national heritage. This was the first case of an industrial building receiving this title. Later, the factory was repurposed as a library, a negotiated solution which was repeated for various other factories in the city. Efforts were also made to include industrial archeology in educational reforms that were taking place at that time as a cross-disciplinary, local history initiative.

Heritage Conservation from Below

In practice, heritage conservation is often reactive, rather than proactive and this is definitely the case in Barcelona with the demolition of the industrial neighborhood of Icaria and its gentrification in preparation for the 1992 Olympic games. This event sparked public consciousness regarding various urban factors which had subsumed conservation efforts: rising property values, top-down urban planning practices, city branding campaigns, real estate speculation, colonial tourism, etc. The Forum de Ribera de Besos was formed in 1992 as a platform to discuss these issues, which returned in force in 1999 in the context of the 22@ urban planning project to revitalize the Poblenou neighborhood of Barcelona, often referred to as the “Manchester Catalan” for its industrial importance.

During this time, a socio-historic discourse of industrial heritage was created as a counter to the dramatic changes imposed in the neighborhood from outside and as a protection of the continuity and authenticity of the neighborhood. The “Salvem Can Ricart” movement brought together factory workers, academics and citizen groups, a coalition for which industrial heritage conservation played a key role as a unifying banner. One result of this movement was the expansion of the heritage list to include 126 elements in the Poblenou neighborhood in 2006.

The Situation Today

A broader impact of these events has been the broadening of the concept of industrial heritage in the city. The discourse has shifted from monument to landscape, from heritage to legacy, opening up possibilities for the heritagization of elements that previously did not count, for example, the casa fabricas in Ciutat Vella. The Museum of History of Barcelona (MUHBA) has also responded by adding industrial heritage sites to its network of musealized spaces in the city, including the Torre de les Aigues de Besos, the Oliva Artes factory in Poblenou, and the Fabra i Coats factory of Sant Andreu. The later has been forecast as the site of a future Museum of Work, planned by the MUHBA to present the social history of industrialization in Barcelona.

Research

The history of “The musealization of Barcelona’s Industrial Past” (the provisional title of this investigation) provides insight into how a city constructs narratives of its past. The story of Barcelona is special in this sense because, in the absence of a centralized museological strategy for preserving these urban memories, alternative approaches have flourished which represent a range of perspectives. Factory workers, engineers, hobbyists, academics, activists, citizen groups, governmental groups, businesses… all have held a vested interest in heritagizing industrial stuff in order to put it to work for them. As Timothy Putnam writes in The Industrial Heritage, “[M]uch of the recognized industrial heritage resource as well as the potential one is a kind of scrapheap; the reasons why it was assembled are often as important or more important a resource than the artifacts themselves.” The case of Barcelona shows that industrial heritage is political. If the city of Barcelona is imagined as a giant industrial museum, the questions become: Who has musealized this industrial stuff? How? And to what ends?

Methodology

Three books have influenced the methodology of this investigation. The first, from the field of Museum Studies, is Industrial Society & its Museums, edited by Brigitte Schroeder-Gudehus in 1992. This collection of essays represents a critical-historical investigation into the museum as a political object: “Why, in a given society, at a given moment, do museums of science, technology and industry come into being? ….What are the primary considerations for those responsible for the creation of museums of science and technology?…. Do museums of science and technology form part of any overall political strategy?” Case studies in this volume range from technical museums in England to Germany to the USA.

Secondly, from the field of Heritage Studies, Tim Putnam and Judith Alfrey‘s book The Industrial Heritage: Managing resources and uses, also from 1992, is based on extensive interviews and research on industrial heritage projects across Europe. Intended as a practical resource, the book offers insight into the process of the construction of industrial heritage, answering questions such as: what can become industrial heritage, what can it do, and how is it created?

Lastly, Heike Oevermann and Harald A. Mieg’s 2015 edited volume, Industrial Heritage Sites in Transformation: Clash of Discourses, looks at mostly urban case studies in which heritage conservation planning efforts compete with other factors such as urban development and architectural production. The authors use synchronic discourse analysis to analyze these perspectives, identifying the differing values, objectives, concepts, and assumptions held.

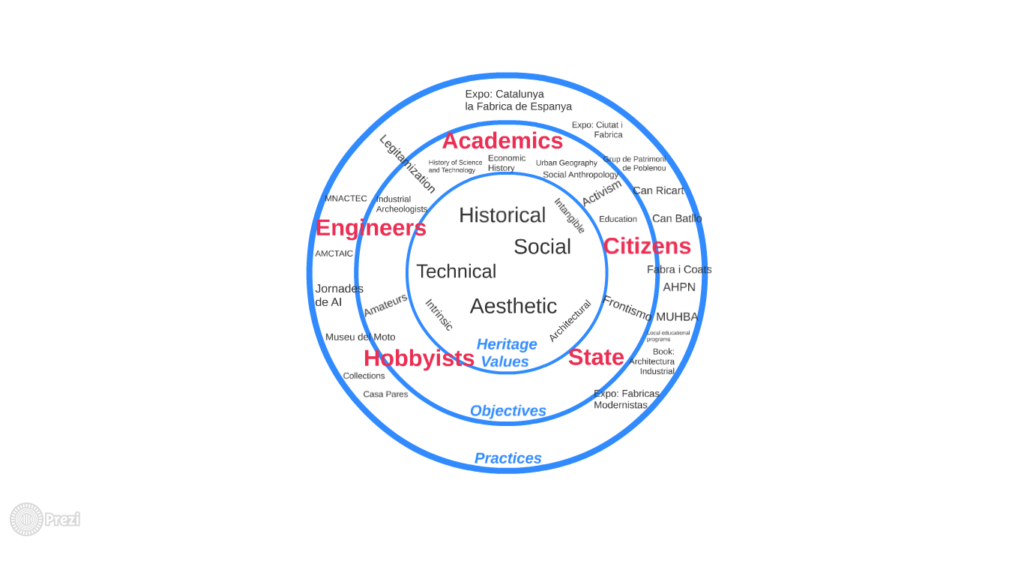

The methodology for this investigation involves a blending of these three approaches, along with resources from the fields of science studies, social anthropology, urban geography, and the digital humanities. A review of the literature in these disciplines, both primary and secondary sources and both specific to Barcelona and in general, has produced the following “values, objectives, and practices spectrum” in which key communities are separated based on their differing heritage discourses. This conceptual tool is helpful in organizing and clarifying the approaches to industrial musealization present in Barcelona and may be used as a skeleton for the final thesis.